Women’s contributions matter and make a material difference to development effectiveness

Women’s economic empowerment and climate action go hand in hand, because women bring different and important perspectives and experiences, as producers, consumers, and as policy and business leaders. That is why women, in their diversity, need to be involved as participants and as leaders.

When women are involved in the ideation and planning, they contribute perspectives on feasibility in production and product design, as well as in logistics and marketing. This includes guiding on the appropriateness of products for different segments of the market. For example, women often know more about consumption and use of products than men, based on their conventional economic roles.

For example, in Bolivia, women face limited opportunities when starting businesses [in the tourism sector], particularly in accessing financing, which prevents them from growing and establishing themselves personally and professionally. Despite these barriers, the sector offers unique opportunities for women. Women are often the ones who make holiday decisions and book activities for families. They are well suited as business leaders of climate-smart eco-tourism ventures. Furthermore, the concept of ‘sorority’ is crucial. There is a growing demand for tourism offerings tailored specifically for women, emphasising safe and enjoyable travel experiences. 1

Women’s access to emergent technologies drives innovation and learning

Women’s different perspectives and learned skills contribute to the more effective functioning of emergent low-carbon, climate-resilient technologies, also. We see this clearly in the case of coastal Kenya, where Integrated Multi Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) is being adopted as an environmental sustainable alternative to conventional fisheries.

IMTA systems involve the cultivation of various species that have mutually beneficial ecological interactions: fish, shellfish, and seaweeds. The waste produced by fish provides a valuable nutrient source for seaweed, which in turn contributes to water purification and the overall health of the ecosystem. Achieng G. et al conclude that IMTA works substantially better when women are involved in all aspects of the business.

Gender inclusivity in the piloting and scaling up of IMTA systems is not just a matter of social justice, they say, but also an entirely pragmatic way to strengthen the achievements and sustainability of its use: “For instance, women are traditionally involved in the processing and marketing segments of aquaculture in many societies, while men are more involved in the cultivation and harvesting aspects.

“By recognising and integrating these gender-specific skills and roles into the Blue Empowerment project, the project has been able to enhance efficiency, productivity, and social equity. This approach ensures that the benefits of the IMTA system, such as economic diversification, environmental sustainability and social well-being, are accessible and equitable across different genders, thereby contributing to the overall resilience and success of the project.” (Achieng, G. et al., 2024, Blue Empowerment Info Brief; page 2).

Women may bring traditional skills and knowledge that are inherently low-carbon and climate-resilient

Socio-cultural norms that have underpinned gendered roles in society can lead to the passing of specific forms of knowledge and skill among women that are highly important in the context of transforming to low-carbon, climate-resilient economies.

In the Philippines, women play a highly significant role in corn farming, according to the ASEAN green recovery through equity and empowerment project. This is evidenced by: “women’s presence in most of the value chain activities, specifically in bringing quality yield attributed to women’s diligent upkeep of the farms using climate-friendly practices” (PPSA and GrowAsia, page 3). More than half of women corn farmers surveyed undertake harvesting, pest control, spraying, pruning and clearing, land maintenance, and transplanting. By doing most of the weeding, they reduce the need for herbicides and so contribute to ecological sustainability, but this work has been fairly invisible to date. Although women’s contributions to climate-smart corn production are critical, they are undervalued. When women are not there to undertake such work, the difference is abundantly clear:

“In Maguindanao, women are leaving the corn farms to find work as domestic helpers abroad. Having fewer women who can do weeding, cleaning, and land maintenance roles (in addition to reproductive functions) leaves the corn fields in a mess. Weeds takeover the corn fields as women’s invisible weeding work becomes no longer available. As a result, from farming white native corn, men are preferring the glyphosate-tolerant high-yielding corn varieties. These varieties are drought-tolerant and so is a form of climate change adaptation but are also input-intensive, costly, and result in higher greenhouse gas (GHG) emission” (PPSA and GrowAsia, page 43).

In Nepal, Forest Action Nepal has supported 18 Indigenous women-led, sustainable, forest-based enterprises to be established, using non timber forest products to create alternatives to plastic bowls, plates and buckets/baskets. The production and sale of these sustainable products is bringing direct economic benefit to the Indigenous and lower-caste women and also bolstering their confidence. The use of the ‘bio bowls and plates’ (Duna-Tapari) and woven baskets is rooted in religious rituals and therefore has a strong local demand and value chain. Their production is based on women’s traditional skills, which are being strengthened and revived in participating communities. Production has provided direct, stable and reliable income to the women producers and has supported the employment of elderly and differently-abled people.

Potential exists for women’s economic empowerment across the landscape of decent, green jobs

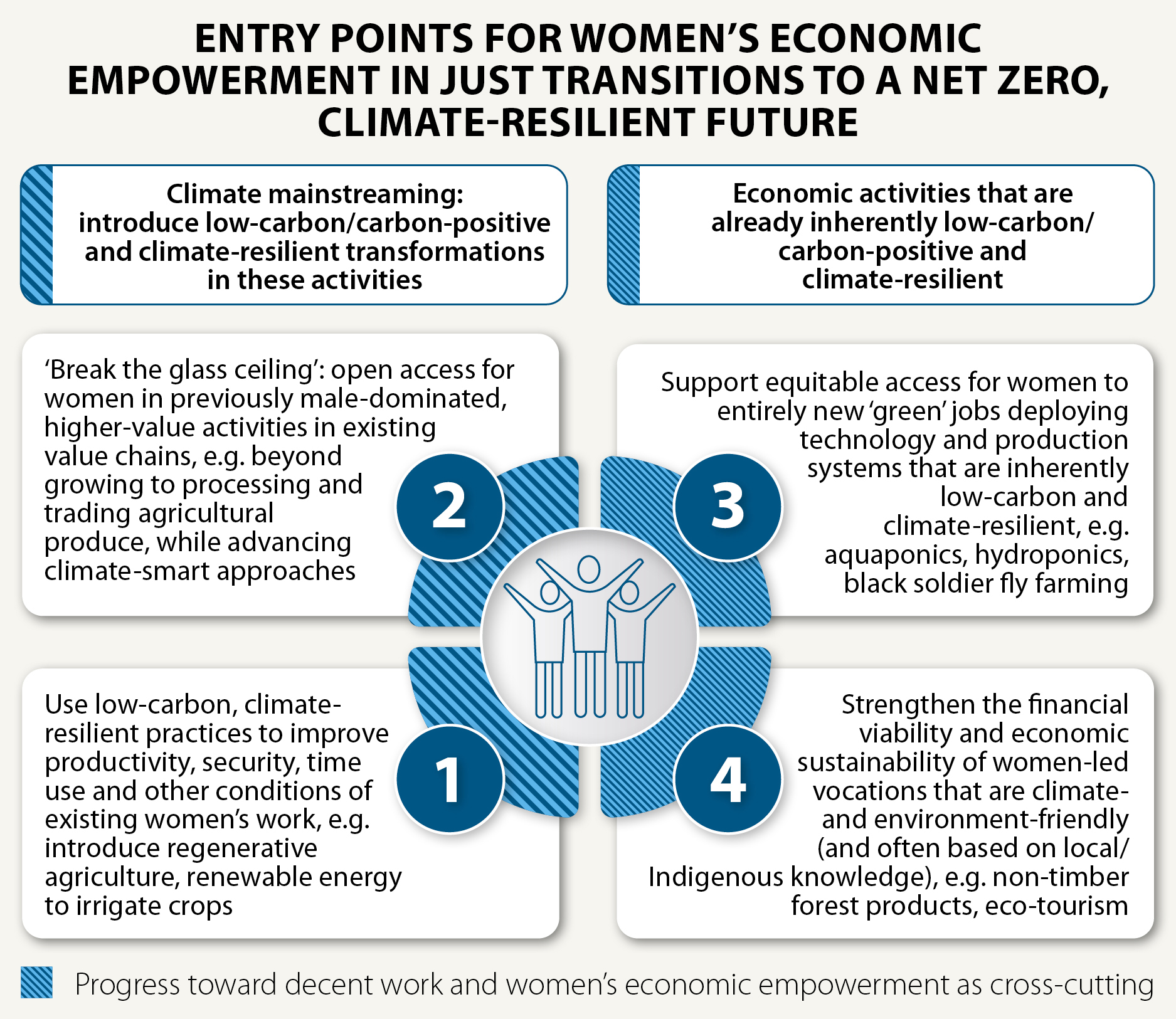

The GLOW action research projects have investigated how to strengthen low-carbon, climate-resilient economic transitions in four broad dimensions, depicted in the figure, below:

- Climate mainstreaming into existing low-productivity and climate-vulnerable activities such as small-holder agriculture, where the introduction of climate-smart management techniques and technologies (such as solar-powered irrigation) can reduce current levels of menial work, improve productivity, yields and stability of income, and make work more rewarding.

- Climate mainstreaming into higher-value activities in agriculture and (agro)forestry value chains, where there is potential for introducing emissions avoidance and climate resilience measures (such as reducing carbon and water footprints across processing, packaging, distribution, marketing and trading activities).

- Consolidating pilots and scaling up businesses based on emergent technologies and production techniques that are inherently low-carbon/carbon-positive and climate-resilient (such as aquaponics, hydroponics and black soldier fly farming).

- Strengthening the financial viability of, consolidating and scaling up businesses based on existing women-led vocations that are inherently low-carbon/carbon-positive and climate-resilient and often based on women’s local and Indigenous skill and knowledge (e.g. sustainable non-timber forest products, forms of community-based eco-tourism).

Women workers may be relatively more concentrated in categories 1 and 4 – although this is highly context-dependent, and social norms may constrain their participation in category 2. Category 3 may be more emergent and open to creating new gender-equitable norms. However, existing societal beliefs around women’s suitability to access new technologies may influence how women’s participation is approached.

The implication of the differential positioning of women in each quadrant (whether a quadrant is currently women-dominated, men-dominated, or emergent) is that any strategies for women’s empowerment will need to address this positioning directly.

The next chapter addresses common challenges, opportunities and recommendations for women’s economic empowerment from across the GLOW programme. Each challenge and recommendation discussed should be interpreted through the women’s positioning in different job areas. For example, the familiar call for women’s increased participation in leadership, as applied to the low-carbon, climate-resilient transition, is especially germane for categories 1, 2 and 3, where women are under-represented as leaders. The call for increased women’s access to productive assets and specific strategies for achieving this is relevant to all four categories, and so on.

Profound potential exists for women’s economic empowerment across all four categories. Their empowerment uniformly promises to catapult forward the low-carbon/carbon-positive and climate-resilient potential in each category of economic activity. Realising this potential relies on deep gender analysis and multi-faceted strategies, tailored to each context.

GLOW programme: entry points for women's economic empowerment in low-carbon, climate resilient transitions

Table of GLOW programme: entry points for woman's economic empowerment in low-carbon, climate-resilient transitions

Footnotes

- ¿Por qué y para qué del enfoque de género en el turismo? Referenced in SDSN and Fundacion IES, April 2024, final report, internal document, page 7