Time to bring gender and climate mainstreaming together

Climate mainstreaming and gender mainstreaming in development have too often been apart. They have been addressed in silos, both by the private sector and by public policy. This was especially so in the immediate shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2020-21, narratives had a strong tendency to call for gender equality in economic recovery, or the ‘greening’ of economic recovery. The two concepts were seldom if ever seriously integrated.

This is clear from government policy and public sector investments, but the divide is also a common feature of private sector efforts, as described by Amar Gokhale:

Thinking through the intersectionality and not focusing on climate or gender as siloed sectors would be key to creating successful outcomes, with a need for capacity building and customisable frameworks at the nexus.

Mainstreaming both gender equality and climate action in policies, programmes and investments means recognising the intersecting dynamics of gender and climate:

- Gender inequality makes climate impacts more severe for some groups of women. Climate change amplifies existing forms of disadvantage and exclusion, because many of spontaneous social responses to impacts are heavily discriminatory (correlating with increased marriage of girls, increased gender-based violence, increased sex trafficking; Global Center on Adaptation and CDKN’s Stories of Resilience 2023 provides many community level examples). This means it is necessary to create systems of empowerment and support for different groups of women and girls depending on their specific climate risk-related vulnerabilities.

- Gender inequality makes it harder for some groups of women to access the climate information, resilience solutions, and low-carbon knowledge, skills and assets they need. Existing gender inequality barriers, compounded by discrimination on the basis of caste, ethnicity, age, differing abilities and marital status, and economic barriers, mean that groups of women need targeted support to access the climate- and sustainability-specific opportunities emerging in local, national, regional and global economies. There is a “growing consensus that the impacts of climate change and non-inclusive climate action have gendered effects and exacerbate gender inequalities in the workplace. These effects consequently harm women, who are the agents of change in building … inclusive opportunities in a low-carbon economy”. (KCI, 2024, page 7)

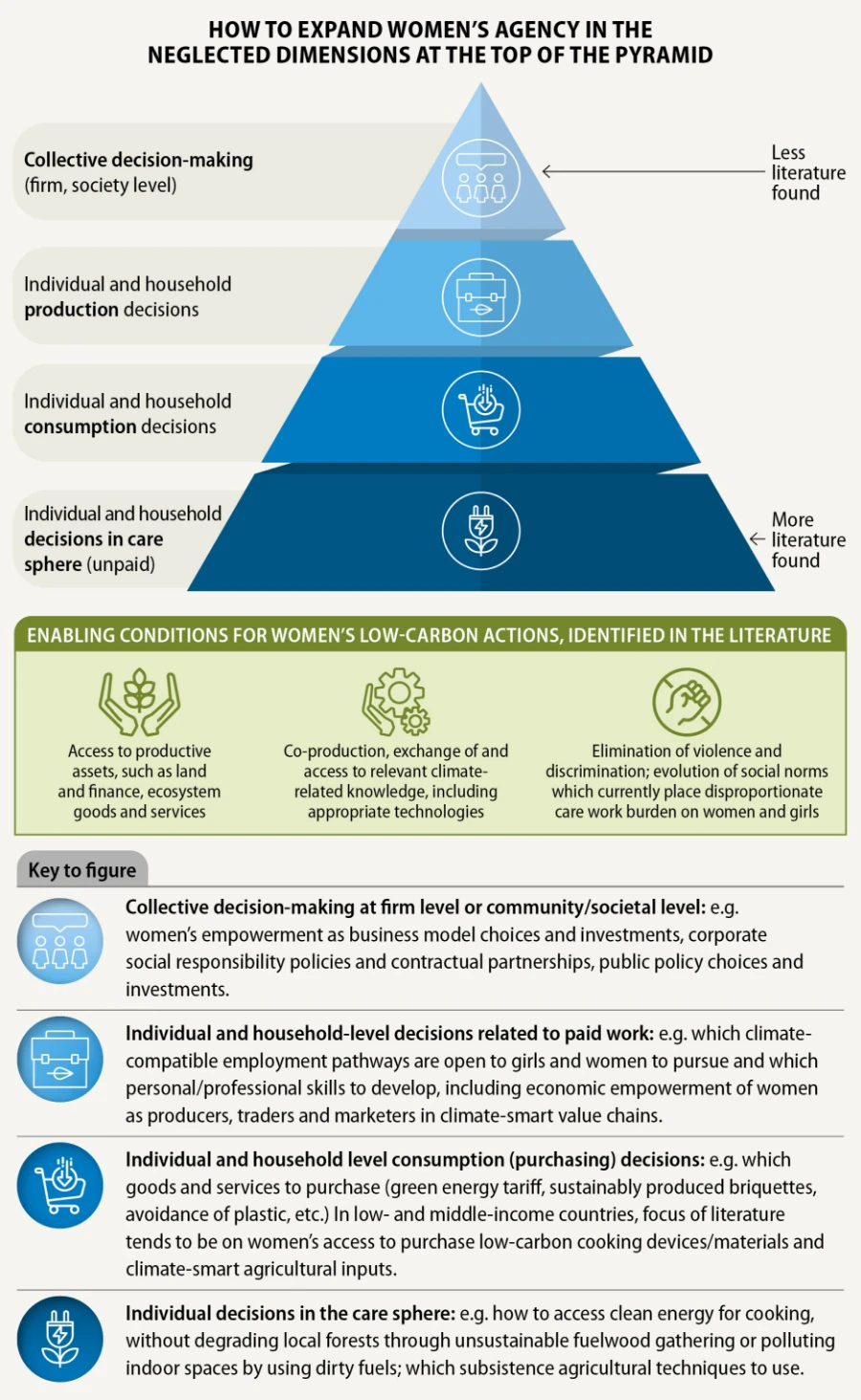

Further, the GLOW programme scanned the literature at the intersection of gender and low-carbon development, and found that women’s roles in climate change mitigation are often narrowly understood. Research and evaluation documents from low-carbon programmes with gender equality goals most frequently describe helping women to fulfil roles as household consumers of low-carbon goods. An illustrative example is the promotion of clean or improved cookstoves. These are highly important and worthwhile endeavours with multiple development benefits (including reducing menial household labour). Still, such programmes have often been devised to maintain the social status quo rather than to advance gender equality.

Far less literature describes active support for women as producers of low-carbon goods and services, or as leaders of low-carbon public policy and private enterprises – that is, advancing women’s economic empowerment to its full potential. There is ample potential for women to participate equally as consumers, producers and public policy and business leaders in shaping low-carbon economies. However, at the moment, women’s participation in these roles assumes a pyramid shape (see figure, below).

Dimensions of women's agency described in literature on 'just transitions'

Dimensions of women's agency described in the literature on just transitionsSource: Dupar and Tan (2023) with permission. View full-size image here

Feminist and Global South perspectives reshape just transitions

The transition to net-zero, climate-resilient economies is the focus of international knowledge-sharing and negotiation efforts under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), driven by countries’ priorities.

In the climate talks, there are two related workstreams. The first of these is the main entry point for GLOW’s research work, with important links to the second:

- The Just Transition Work Programme.

- The impact of the implementation of response measures work under the climate change mitigation pillar of the convention and Paris Agreement.

The ‘Impact of the implementation of response measures’ workstream came earlier, and sought to identify the socioeconomic impacts of climate change mitigation measures: “These impacts could be positive or negative, therefore the Convention, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement seek to minimise the negative and maximise the positive impacts of implementation of mitigation policies and actions.” (UNFCCC)

This workstream has tended to focus especially on energy transitions: both production and consumption. It covers workers who are being displaced by shifts from fossil fuel extraction to low-carbon energy production. This includes compensation, reskilling, retraining and redeployment of workers from occupations such as coal mining, into greener alternatives. It also covers policy instruments that can protect low-income and economically-vulnerable consumers during the phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies and the promotion of cleaner fuels.

As described by Dupar and Tan (2023), the tenor of discussions tended to be around workforce redeployment. This framing eclipsed the needs of workers who start in the most disadvantaged positions, including women, informal sector, and rural workers in the Global South, and need to progress into more secure, low-carbon and climate-resilient jobs, including in the same sector albeit under safer and more climate-compatible conditions. Also, this framing, and its coverage in the broader international literature, has been shallow in terms of exploring the socioeconomic impacts of the low-carbon transition, beyond the formal workforce into informal work, and in other dimensions of livelihood and socioeconomic wellbeing.

The just transition narrative has grown out of and benefitted from, challenges by diverse Global South voices to the narrower focus of the ‘impact of implementation of response measures’ discussion.

"Sustainable and just solutions to the climate crisis must be founded on meaningful and effective social dialogue and participation of all stakeholders..."

As a consequence, the mandate for the UNFCCC’s Just Transition Work Programme was decided at COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh (2022) and operationalised at COP28 in UAE (2023). It reflects the appetite among governments and civil society movements, especially those rooted in the Global South, to address socioeconomic transition issues from a much wider perspective. Governments’ decisions under the Sharm El Sheikh Implementation Plan state as follows:

“50. Affirms that sustainable and just solutions to the climate crisis must be founded on meaningful and effective social dialogue and participation of all stakeholders and notes that the global transition to low emissions provides opportunities and challenges for sustainable economic development and poverty eradication; 51. Emphasizes that just and equitable transition encompasses pathways that include energy, socioeconomic, workforce and other dimensions, all of which must be based on nationally defined development priorities and include social protection so as to mitigate potential impacts associated with the transition, and highlights the important role of the instruments related to social solidarity and protection in mitigating the impacts of applied measures; 52. Decides to establish a work programme on just transition for discussion of pathways to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement outlined in Article 2, paragraph 1, in the context of Article 2, paragraph 2” (Source: Decision 1/CMA.3, paragraphs 50-52).

“85. Encourages Parties to increase the full, meaningful and equal participation of women in climate action and to ensure gender-responsive implementation and means of implementation, including by fully implementing the Lima work programme on gender and its gender action plan, to raise climate ambition and achieve climate goals”(Source: Decision 1/CMA.3, paragraphs 85).

The UNFCCC’s Just Transitions Work Programme opens the door to discussing how education, information, skills training, social protection support, and access to productive assets can be extended fairly and equitably to workers and small businesses in low-paying, unsafe, insecure work that is both highly economically vulnerable and climate vulnerable in diverse development contexts.

The modalities for the Just Transition work programme include:

- at least two dialogues for Parties and Observers, each year, on just transition issues, which will feed into the annual high-level ministerial meeting on just transitions

- a text on just transitions at each Conference of the Parties (COP)

- a growing body of evidence to inform the second global stocktake of progress in implementing the Paris Agreement.

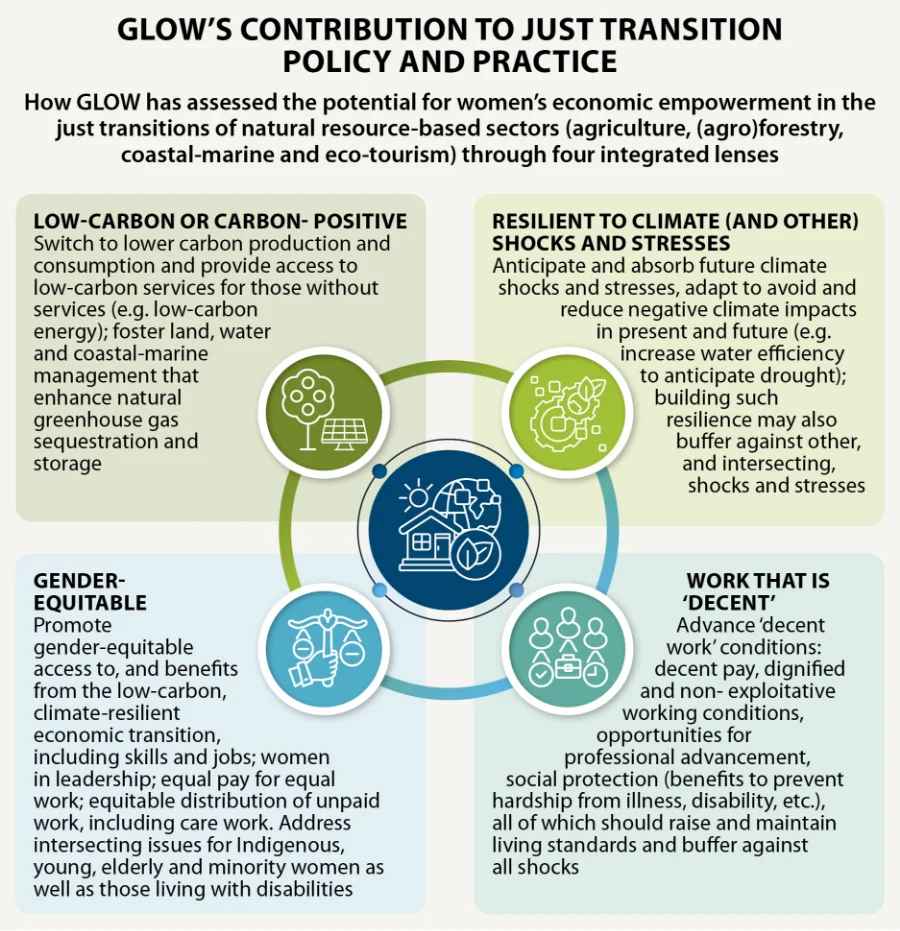

The GLOW programme’s contribution is to present analysis from diverse developing countries on advancing gender equality in the just transition, along with pragmatic and empirically-tested recommendations for policy and practice.

Eco-tourism trainees, Bolivia (c) SDSN Bolivia

About this report

Based on evidence from the GLOW programme, this report tells the story of women and men in largely rural and peri-urban locations in the Global South who are mostly not retraining from coal mining jobs, or switching from dirty diesel generators or chemical nitrogen-based fertilisers. They are starting from a position of economic disempowerment due to a lack of material inputs, finance and productive assets for their livelihoods and businesses. They are trying to gain access to energy and inputs because they lack them almost completely.

They want the means for decent, productive livelihoods and are willing to leapfrog polluting conventional methods to embrace low-carbon and climate-resilient means.

The projects range from women horticulturalists in Senegal and Guinea who want access to solar-powered irrigation to overcome the tedious, time-consuming work of manual irrigation, to women advancing their economic empowerment in Cameroon by restoring the health and fertility of depleted, unproductive lands.

They range from involving women in the scaling up of emergent technologies such as Integrated Multi Trophic Aquaculture in Kenya to demonstrate both its ecological-climate sustainability and economic empowerment potential, to women leading the revival of indigenous and local craft-making for local markets in Nepal.

The women’s empowerment perspective is heavily shaped by geography, class and socioeconomic status, and existing types and levels of production and consumption. All are framed by structural aspects of national economies, and by opportunity spaces in national policy for managing just transitions.

However, a common thread runs through all the stories: We currently see a world where economic transition policy narratives, policies and investments have until recently been dominated by Global North, male-dominated industries. The world we want to see is one where women are co-leading, benefiting fairly and equitably from just transitions, and being provided with adequate resources to achieve this. This report discusses how we can achieve this vision.

Diagram of GLOW's contribution to just transition policy and practice

Diagram of GLOW's contribution to just transition policy and practice