Net zero is the frame for global development

It is a matter of urgency to transform the global economy into a net zero economy – in which we cut or avoid creating greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel use, land use change and other sources. In this world, we embrace ultra-low emissions production and consumption. We cancel out our remaining emissions to reach net zero, primarily (although not exclusively) by locking up greenhouse gases in carbon-rich ecosystems such as healthy forests, wetlands and soils.

It is urgent because greenhouse gas emissions from human activity are driving climate change that has led to “widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people” in all world regions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Already, increasing frequency and intensity of droughts and heatwaves are causing crop losses, tree deaths and risks to workers’ health and productivity. (IPCC 2022 B5) This is today’s reality.

The world is way off track to meet the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement: to limit average global temperature rise to 1.5oC. Average warming is already 1.1oC above pre-industrial levels, and the extent of present climate-related losses and damages is greater than scientists had anticipated. At average global warming above 1.5oC, the risks to vulnerable social and ecological systems are very high indeed.

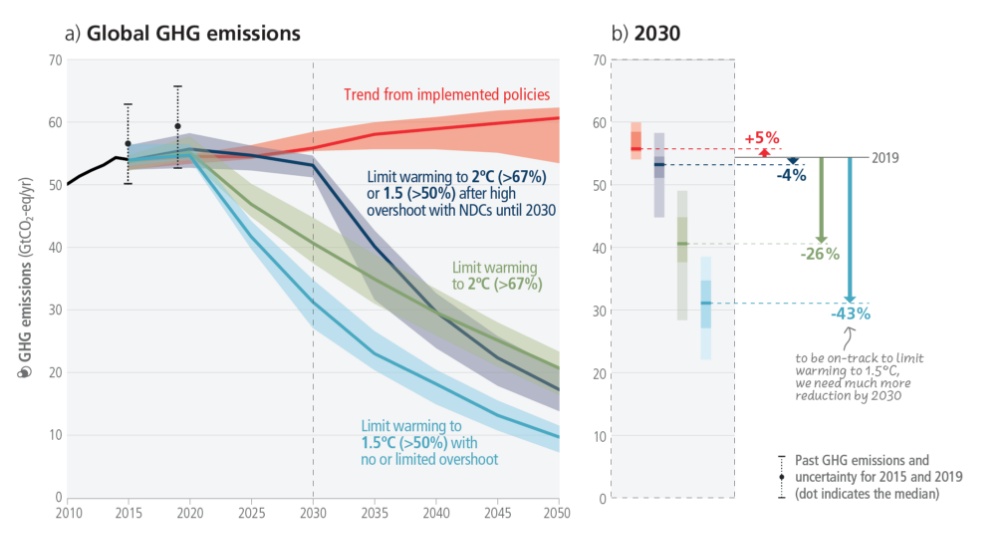

In spite of this, global emissions continue to rise year on year. From a small dip in emissions during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, emissions are now higher than ever before. Global emissions must decline irreversibly by 2025 and be at least 43% (below 2019 levels) by 2030 (see Figure) – to get back on track. It is a tall order.

Governments’ international commitments to reduce or avoid emissions, the ‘NDCs’: Nationally Determined Contributions collectively fall far short of this need. They add up to a greenhouse gas emissions pathway of 2.9oC of global warming – or 2.5oC of warming if developing countries get international support for their climate plans. 1

Global emissions: A visual overview of current trends and future challenges

Read moreRapid and heavy emissions cuts are needed for a 1.5°C world

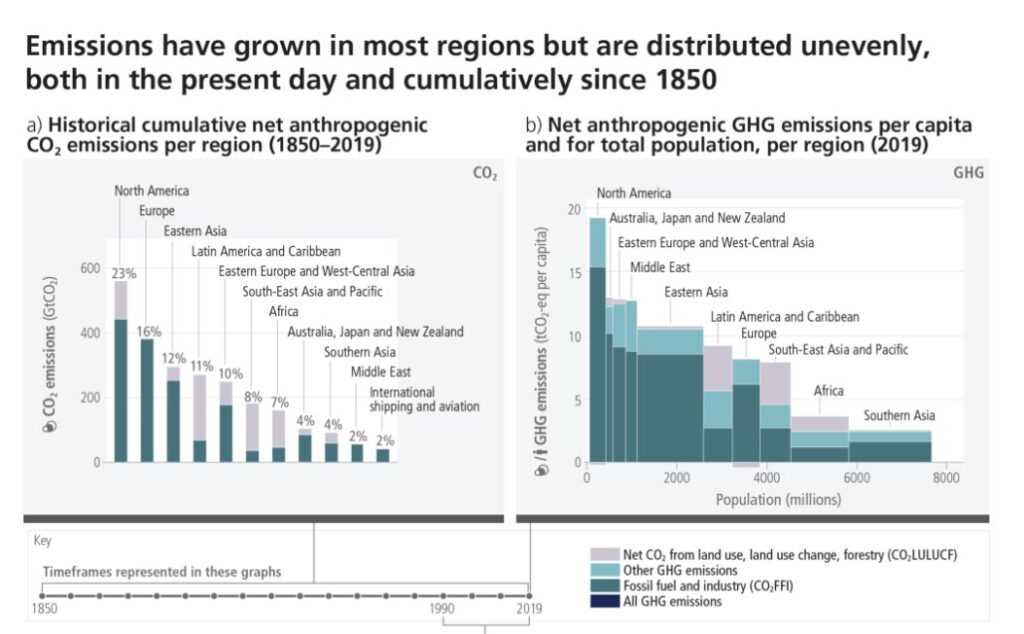

Emissions have grown in most regions but are distributed unevenly, both in the present day and cumulatively since 1850

Inventory of forest flora, Nepal (c) Usha Thakuri

Gender and social inclusion shape risk and resilience

Climate change is already laden with historic injustices: countries that are hardest hit by climate change impacts are the least developed countries and small island states that have generated the fewest emissions.

Within countries, different groups of people are also more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change because of their social and economic status, including the assets they own and control and sociocultural norms that shape their exercise of rights:

“Regions and people with considerable development constraints have high vulnerability to climatic hazards (high confidence)…Vulnerability at different spatial levels is exacerbated by inequity and marginalisation linked to gender, ethnicity, low income or combinations thereof (high confidence), especially for many Indigenous Peoples and local communities (high confidence). Present development challenges causing high vulnerability are influenced by historical and ongoing patterns of inequity such as colonialism, especially for many Indigenous Peoples and local communities (high confidence).” IPCC, Working Group II, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Summary for Policy Makers, B.2.4.

This landscape of climate-related losses and damages is already a feature of today’s world. Notwithstanding, further climate change impacts may be expected beyond present levels. Even if economies shifted onto a global trajectory toward 1.5oC today, warming would continue to increase at least until 2040, with associated impacts (IPCC 2022, Figure SPM3). There is an urgent need for enhanced resilience and adaptive capacity at all scales to address current and future climate risks.

Climate change and social inequity are often described as interacting negatively with each other to ‘compound’ risk. People are more vulnerable to climate hazards when they are less educated, healthy, politically empowered and economically secure. They are more resilient when they gain these qualities. Where discrimination exists in society, as it does in many places against women and other social groups, then climate shocks and stresses may elicit spontaneous, discriminatory responses, such as gender-based violence. In this way, climate hazards – more frequent and intense as a result of climate change – can act as an amplifier of harm. Understanding the underlying social and economic inequalities and how they contribute to climate vulnerability and risk is the key to crafting socially and gender-just interventions that also address the causes and consequences of climate change.

Gender inequality: the crucial context

The existing extent of gender inequality forms the crucial backdrop for climate action. Gender equality is a human right and has a basis in international law and in the national legislation of most countries in the world. Gender equality is also inextricably linked to economic performance and human development.

UNDP’s Gender Development Index tracks the disparity between women’s and men’s attainment of longevity, education and income per capita. On these combined measures, some countries are at parity, but many countries have a marked gap of 15 percentage points or more, especially in education and income. UNDP’s Gender Inequality Index tracks gender equality based on indicators of reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market. It illuminates deep disparities between men and women, boys and girls, by country.

Globally, the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index tracks the gender development gap between women and men in economic, political and education spheres and finds that at current rates of progress, it will take 134 years to close the gender gap.

These indices showed gender inequality shoot up during the Covid-19 pandemic, when women lost paid work more quickly, more girls than boys dropped out of school entirely, and women and girls assumed even more unpaid care work.

These setbacks have largely been recovered, but still, WEF’s Global Gender Gap Index 2024 shows that gender equality has barely budged for almost two decades, on global average.

The drivers of gender inequality, and barriers and opportunities for women’s economic empowerment, are specific to context. As UNDP highlights, gender inequalities are complex, and it takes sophisticated analysis to understand and address them adequately. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. This is especially so when promoting gender equality in the context of climate action, whether it is climate change mitigation, adaptation or both.

For this reason, this report dedicates a whole chapter (Chapter 3) to discussing exactly how gender equality, economic development and climate action intersect in each GLOW country and sector. Furthermore, opportunities for women are shaped by their income and education, ethnicity, indigeneity, marital status, age, different abilities and other factors. Where GLOW projects have analysed the barriers and opportunities for specific groups of women based on intersectionality, the report identifies learning from this to illuminate how approaches can be tailored to diverse circumstances.

GLOW’s vision

Gender Equality in a Low Carbon World (GLOW), 2021-2024, is a programme funded by the International Development Research Centre, which seeks to bring the two critical goals of sufficient action on climate change and gender equality together in an integrated vision and practical insights and recommendations for mutual progress. It supports research on promising women-led solutions for green economies and climate action.

GLOW was launched as the world reeled from the Covid-19 pandemic and global GDP had nose-dived. Governments and international bodies, including development finance institutions, were considering what fiscal measures and targeted investments were needed to aid countries’ recoveries and to support the worst-hit sectors and sections of the population. They were also considering whether it was possible to ‘build back better’ from the pandemic in ways that would catapult forward the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Twelve GLOW action research projects were selected following an open, competitive call based on their relevance to local challenges and clear plans to influence policies and actions.

The research projects spanned 16 countries: Bolivia, Cambodia, Cameroon, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Nepal, Nicaragua, Philippines, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda and Vietnam. It also included the Palestinian territory of Gaza, where work was halted due to the conflict.

The GLOW projects explore innovations for women’s economic empowerment and climate action in agriculture, forestry and agroforestry, aquaculture, land restoration and tourism. They are led by local research experts, who work hand-in-hand with the people in government, business and civil society who can implement solutions.

Difficult labour of a woman coffee farmer, Colombia (c) Neil Palmer CIAT

Women’s economic empowerment in the Global South

GLOW’s research has sought to examine how women can be economically empowered through economic transitions to more climate-compatible, sustainable production systems.

There is not a single definition of women’s economic empowerment, but most definitions encompass the following dimensions:

- labour market participation

- quality of work (including income levels, security/reliability of work, etc.)

- access to skills development

- agency (decision-making power over economic assets, lives and well-being at multiple levels: family, micro, meso and macro levels)

- resources (legal, financial, and social enablers that enable women to do decent work).

- care economy (tasks considered work, rather than leisure, that are unpaid and/or inequitably allocated between the sexes).

Source: Dupar and Tan, 2023, From low-carbon consumers to climate leaders: page 2.

The reality is that many modes of work merely enable people to survive from day to day, such as through casual labour or low-productivity, smallholder agriculture. For instance, in East Africa, Intellecap describe how women make up half of the agricultural workforce and “women employed in the sector contend with low pay, informality, inferior working conditions and lack of social protection”.2 There needs to be a shift to “allow real incomes and capabilities to be enhanced and capital accumulated, and… rebalance social injustices, such as gender inequalities (Sumberg and Okali, 267-277, in Dupar et al 2021 page 6).

The aim of providing women with ‘decent work’ is a thread throughout this report, which links the definitions of women’s economic empowerment in the literature to the Sustainable Development Goals and other international policy frameworks. The International Labour Organization defines decent work as:

“Decent work sums up the aspirations of people in their working lives. It involves opportunities for work that is productive and delivers a fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for all, better prospects for personal development and social integration, freedom for people to express their concerns, organise and participate in the decisions that affect their lives and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men.” (Source: ILO, 2024)

The GLOW findings discuss in applied context how women’s work can be made more ‘decent’ through better pay and security of income, more dignified and less demeaning conditions, access to and reliability of support during sickness or disability, and support for dependents.

These aspirations and goals support Agenda 2030’s SDG 8, Decent work and economic growth and its integration with SDG 5: Gender equality, and SDG 13, Climate action.

GLOW’s focal sectors of agriculture, forestry and agroforestry, aquaculture, land restoration and tourism also align with SDG 2: Zero hunger (incorporating sustainable agriculture), SDG 12: Sustainable production and consumption, and SDG 15: Life on land.

Geneplus livestock value chain workers explain climate-smart measures (c) Intellecap

The synergies between women’s empowerment and sustainable development are also increasingly recognised in business. For small and large business leaders, the financial imperative for women’s empowerment is clear. When women are empowered, businesses can access a talented worker pool more readily. Women’s leadership in low-carbon and climate-resilient enterprises strengthens the value proposition of businesses. It frequently endows businesses with a deeper understanding and connection with their consumer base. These themes resonate deeply throughout this report and are unpacked through case study examples.

The original GLOW research, literature and policy scans have also highlighted how low-carbon development processes and the multiple dimensions of resilience are fundamental to women’s economic empowerment. The GLOW programme was rightly premised on the risk that gender-blind shifts from high-carbon to low-carbon (or net zero) production systems could risk marginalising women unless they were fully involved as leaders and participants in the transition. All the evidence in this report underlines that initial premise.

The research has also revealed the importance of understanding women’s resilience to climate shocks and stresses 3 and all its economic, social and psychological dimensions, as part of women’s economic empowerment in the present era.

Resilience emerged organically to be a towering issue in projects’ contexts – because of the significant climate risks 4 and impacts 5 and broader economic shockwaves (e.g. arising from the Covid-19 pandemic) that emanate through natural resource-dependent economies.

In these landscapes and economic sectors, it is not easy and practical, nor desirable, to separate the ‘low-carbon’ from the ‘resilient’, whether it is resilience to climate shocks and stresses such as drought, floods, heatwaves, ice melt, erratic rainfall, sea level rise, or resilience to other external shocks, such as pandemics and wars. The opportunity exists to combine emissions avoidance with heightened resilience. Accordingly, the findings from the GLOW action research projects are not just about low-carbon development, but they also take a pragmatic approach to resilience, including the resilience of both ecosystems and of people and their livelihoods. The conclusions and recommendations bridge these multiple aspects.

About the terminology in this report

Read moreIn this report, ‘low-carbon’ is a shorthand term. Given that the need is for a ‘net-zero carbon’ trajectory for the global economy to be achieved by the mid-21st century, a higher level of ambition is required for the land use sectors that are the focus of this report. When we refer to ‘low-carbon’ practices, these may in many cases incorporate land, forest and coastal management that captures carbon and other greenhouse gases from the air and locks them up in soils and vegetation.

‘Climate resilience’ is a shorthand in this report. It refers not only to the practices that enable economic production systems to withstand, absorb and recover from climate shocks and stresses. ‘Climate-resilience’ also includes practices that help ecosystems and diverse species to withstand climate risks. It encompasses the notion of ‘nature-positive’ action in line with the Global Biodiversity Framework. GLOW projects were generally not framed to address biodiversity explicitly. So, there are gaps in evidence around the impacts of the GLOW activities on ecosystems and biodiversity – but where there is evidence, it is foregrounded here.

Footnotes

- Countries with high emissions must reduce their emissions; developing countries with small per capita emissions calculate how many emissions they would avoid by taking a low-carbon trajectory, versus a ‘business as usual’ trajectory.

- Yadav et al, August 2024, p7

- Resilience can be defined as the ability to adapt to, anticipate and absorb climate shocks and stresses.

- The potential for adverse consequences for human or ecological systems, recognizing the diversity of values and objectives associated with such systems. In the context of climate change, risks can arise from potential impacts of climate change as well as human responses to climate change. Source: IPCC AR6 Glossary.

- The consequences of realized risks on natural and human systems, where risks result from the interactions of climate-related hazards (including extreme weather/climate events), exposure, and vulnerability. Impacts generally refer to effects on lives, livelihoods, health and well-being, ecosystems and species, economic, social and cultural assets, services (including ecosystem services), and infrastructure. Impacts may be referred to as consequences or outcomes and can be adverse or beneficial. Source: IPCC AR6 Glossary.